It was almost 70 years ago that Lionel Barber arrived in Pembroke. He came to play hockey and never left. On Sunday, November 8, 2020 he took his final breath in the community he adopted as his home so many years ago.

His death was not unexpected as Barber had been diagnosed with colon cancer a few years ago and had opted not to take any treatments. His passing leaves a big hole in the Lumber Kings fraternity and breaks a link to Pembroke’s rich hockey history.

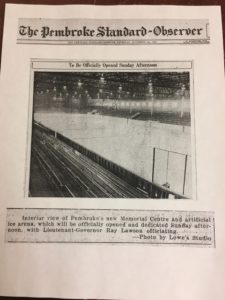

Growing up in the Toronto area, Barber was a tenacious junior hockey player, good enough to capture the interest of the Toronto Maple Leafs, but his hockey career would not lead him to Maple Leaf Gardens. Instead, he would suit up with the Pembroke Senior Lumber Kings for the 1951-52 season, where he would help christen the new Pembroke Memorial Centre.

The 1950’s were both exciting and precarious for Pembroke’s senior hockey team. In Barber’s first season with the Senior Lumber Kings, the team made it to the Eastern Canadian Allan Cup semi-finals, but by the late 1950’s the club was struggling to stay alive. Rising player salaries, increased operating costs and the influence of television made it difficult for the club to pay its bills.

‘They had a payroll here as high as some American Hockey League teams,” Barber told me the last time we spoke on the phone, just a few days before he passed away.

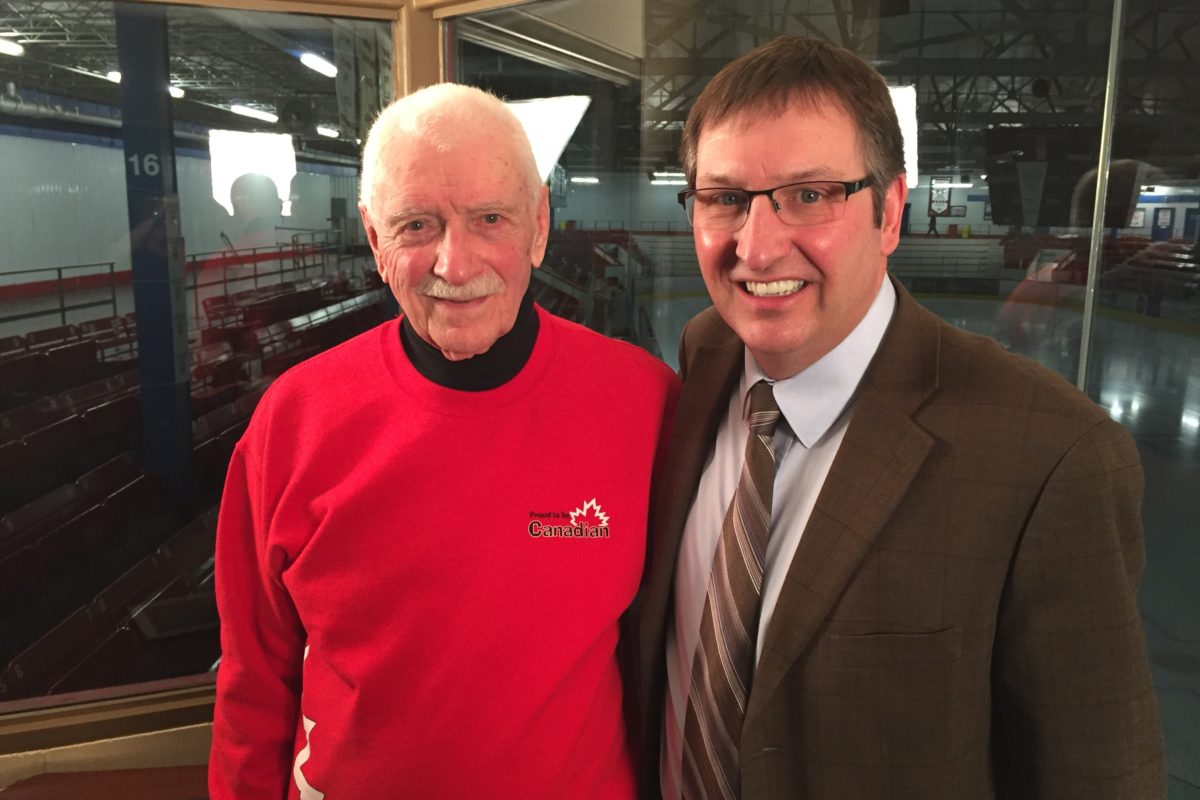

It was in the spring of 2016 that I sat down with Barber in a private suite at the Memorial Centre to interview him about the glory years of senior hockey in Pembroke. Always a tremendous storyteller, Barber brought me into a time when there were only six teams in the National Hockey League, and small towns across Canada placed their senior teams on a pedestal.

As he reminisced about a special time in his life, he spoke of the great players he suited up with like Roy, Bruce and Bert Giesebrecht, or his playing coach, Cully Simon, who on opening night at the PMC gave Barber the assignment of covering Maurice “The Rocket” Richard. The Montreal Canadiens had travelled to Pembroke to play an exhibition game on November 14, 1951 and the opening night affair had drawn a sell out crowd to the newly minted Memorial Centre, which after two years of construction and a significant fund raising effort had become the pride of the community.

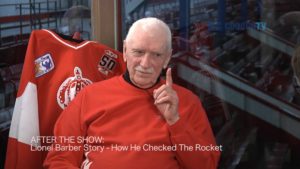

It was Barber’s story of how he had been duped by Richard that sparked my interest in writing a book about Pembroke’s hockey history. As the youngest player on the Pembroke squad, Barber had been told by Simon to stick with Richard wherever he was on the ice, and so he did, but he learned very quickly why Richard was called “the Rocket.”

With the Canadiens on a powerplay, Richard did something that Barber had never seen in a hockey game. He left the offensive zone and carried the puck to centre ice. Barber chased after him. So did Richard’s teammates. They knew what was coming.

With Barber trailing him, Richard quickly turned on his jets, bursting into the Pembroke zone. He flipped the puck to Elmer Lach who quickly returned it to Richard and wham, the puck was in the back of the net. It all happened so quickly and the large crowd was mesmerized by the skill and speed of one of hockey’s most prolific goal scorers.

That was Barber’s introduction to Pembroke’s rabid hockey fan base. He had come to Pembroke on a whim. After winning a memorial cup junior title with the Barrie Flyers, he tried out for the Quebec Aces, a minor league team playing out of Quebec City. After practice one day he was told by the coach, Punch Imlach, that he had been cut from the team. As he sat dejected in the dressing room taking off his equipment, Barber would meet a man who would change his life.

Art Bogart was the crafty general manager of the Pembroke Senior Lumber Kings. He had travelled to Quebec City in the hopes of picking up some players for his team. He asked Barber if he’d like to play in Pembroke. Barber said the first thing that came into his mind, “Are there any pretty girls in Pembroke?” When Bogart answered enthusiastically, Barber was on his way to the town, later to become a city, where he would live for the rest of his life.

Barber was barely 20 years old when he took Bogart’s bait. He had lost his father to a heart attack a couple years earlier and he found Pembroke to be a nice community where he quickly settled into the life of a senior hockey player in small town Canada. He got himself a job selling cars, he married and had four children, and he developed a mental toughness that defined him as an athlete, father and businessman.

He wasn’t afraid to share his opinion, but he believed strongly in treating people well and earned a reputation for being fair in the highly competitive business of selling cars. When he wasn’t working or spending time with his children, Barber loved to play golf and enjoyed coaching minor hockey. After he stepped aside from playing competitive hockey, he continued to enjoy the sport at a recreational level.

Our link was hockey. I truly enjoyed hearing his stories about the senior Lumber Kings, even if I had heard them before. There were always a few extra nuggets thrown in that captured my attention, but as his health failed, most of our conversations weren’t about the sport we mutually loved. They were about life.

He shared openly, saying “Very few people have lived a fuller life than I have,” and when I asked him the difficult question of how he wanted to be remembered, he focused on his family. “As a real good father who had four great kids and many Grandchildren. My biggest success was my family,” Barber said.

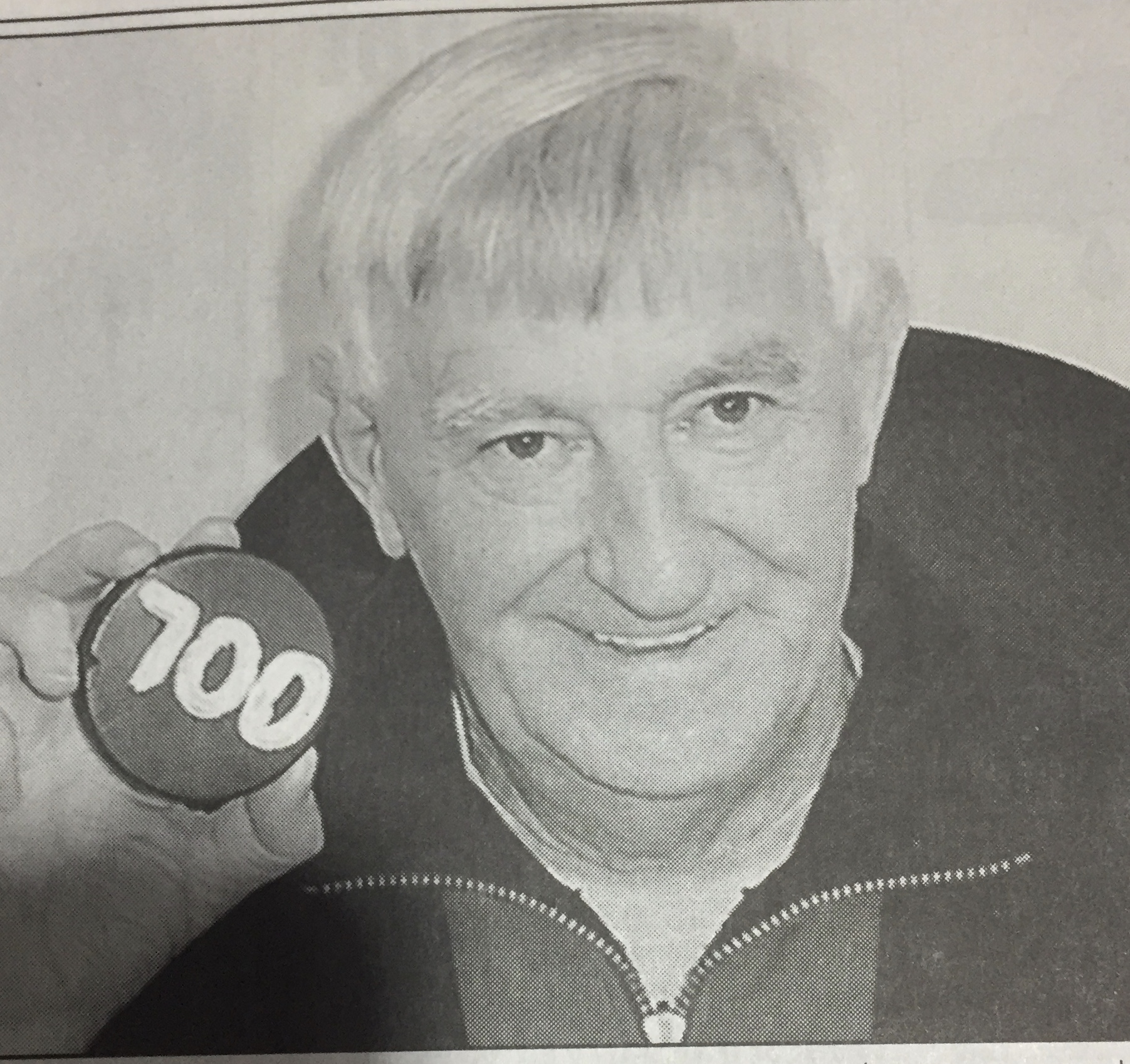

Lionel Barber died at his home, surrounded by his family. A few weeks earlier he had celebrated his 89th birthday, telling me how pleased he was to have lived into his 90th year, but acknowledging that he knew his time on earth was coming to an end. “I’m a realist,” he said, in the matter of fact tone that I had come to know well during our phone conversations when the subject moved from hockey to mortality.

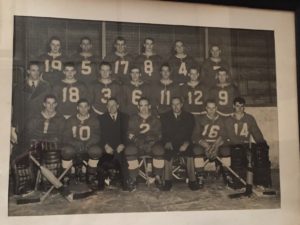

In my basement, a picture of the 1951-52 Pembroke Senior Lumber Kings hangs on the wall. A very young Barber is standing in the middle row wearing jersey number 18. The black and white photograph was no doubt taken at the PMC around the time that Barber had made his Lumber Kings debut, trying to keep up with “Rocket Richard.”

That picture has always been very special to me. It was Lionel who first shared it with me over a cup of tea at his home. His stories brought the photograph to life as he shared with great enthusiasm tales of the characters and circumstances that made Pembroke one of Canada’s greatest hockey towns.

Lionel Barber will always be very special to me. I’ll miss him, but I’ll celebrate his legacy as one of Pembroke’s greatest hockey players and a dear friend. Perhaps now he’ll have the chance to catch the Rocket. I’m sure the Hockey Gods will be on his side.

(Jamie Bramburger is the author of Go Kings Go! A Century of Pembroke Lumber Kings Hockey, a book that was inspired by Lionel Barber’s hockey stories.)