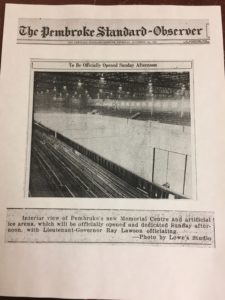

Morris Snider was busy. As the first manager of the new Pembroke Memorial Centre he was expected to turn the new arena into a profitable enterprise, especially after the town of Pembroke had needed to hold a referendum to get the blessing of taxpayers to borrow the final $125,000 to finish the building.

In the early 1950’s, new arenas were being built in many communities as the need for artificial ice become paramount for senior and junior hockey teams to financially survive, but modern buildings also created new business opportunities. As Pembroke considered how it would turn its new arena into a twelve month a year operation, the town set up a commission to run the Memorial Centre, choosing Snider for that job.

It was a controversial decision. Snider had been the manager of the Centre Theatre in downtown Pembroke. He was a hockey enthusiast but his career had been restricted to the theatre business. He was also a relative newcomer to Pembroke having taken the Centre Theatre job in 1948.

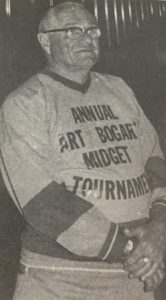

The man that many Pembroke residents expected would get the job was Art Bogart, who for decades had been managing the Mackay Street Arena and also the Senior Lumber Kings. Many locals felt Bogart had the pedigree to seamlessly move into the role, but Snider brought a different type of business experience and with pressure to have a steady flow of bookings at the PMC, it was thought Snider’s connections in the theatre world would allow him to attract a broader array of entertainment.

So, to ensure the new rink got off to a good start Snider would rely heavily on his director of maintenance, Bert Barr, who would be counted on to have the rink ready for its grand opening on November 14, 1951 when the Montreal Canadiens came to town to face the Senior Lumber Kings. There was a lot to do and there were plenty of problems to solve, including an ongoing electrical issue that had resulted in several power outages as the Senior Lumber Kings started playing games and holding practices in the arena.

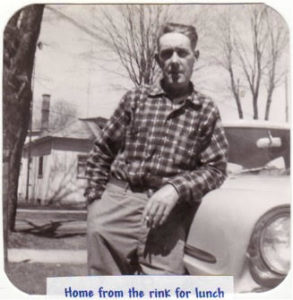

Barr had worked as a carpenter and forester before taking the job. He was a handyman who had a knack for fixing things and in the lead up to the rink’s opening he was putting in long hours. There was a lot of last-minute construction and he was a novice at making artificial ice, but Barr was a problem solver and a worker. He couldn’t do it all, so he enlisted some help, primarily from Ken Campbell of the Senior Lumber Kings and Bill Higginson, a youngster who loved hanging around the rink.

While Barr got some rest, Campbell and Higginson would work the night shift, flooding the surface. When Barr arrived for work the next morning he’d inspect the ice and make the necessary adjustments in the ice making plant to ensure the best possible skating conditions for games. Campbell and Higginson helped with that too, going for a skate in the middle of the night, becoming the first two people to ever skate in the Memorial Centre.

Barr could be gruff, but he also had a sense of humour. Family was important to him but so was his job. He loved to sit in the boiler room at the PMC and talk hockey. His enthusiasm for the sport wore off on his three sons, Bob, Bert and Ron who all played for the Junior Lumber Kings, their Dad rarely missing a game.

The contributions made by Barr in the early years of the Memorial Centre were significant. His ice making ability made him indispensable and while he grumbled when the Zamboni arrived in the 1960’s, Barr knew that progress was inevitable. It was progress that had brought him to the job of chief ice maker at the PMC, as the new arena brought with it the marvel of artificial ice.

When he passed away on June 3, 1974 in his 63rd year, the tributes poured in for Bert Barr. In the Pembroke Observer, Harold Garton wrote, “Goodbye old friend, I hope there are no Zambonis where you are now. You wouldn’t be happy without your crew of rink rats.”

Barr spent thousands of hours in the bowels of the Pembroke Memorial Centre. He often worked in solitude, preferring to stay out of the limelight. 70 years after the PMC opened, Barr’s fingerprints remain throughout the building that he helped christen.