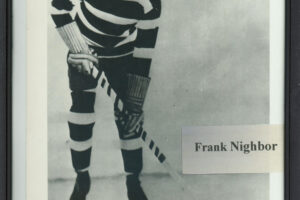

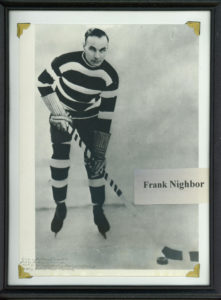

It has been 90 years since Frank Nighbor laced up a pair of skates in a professional hockey game. It has been 67 years since he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame and it has been almost 55 years since he died.

The “Pembroke Peach,” as Nighbor was known, is recognized as one of the best to ever play the game. He won five Stanley Cups, four with the original Ottawa Senators, won the Hart trophy as the league’s best player and he was the first recipient of the Lady Byng trophy for sportsmanlike and gentlemanly play.

Nighbor is credited with mastering the poke check, or as it was better known in his era, the “hook check.” He never received a major penalty in his career, and the Ottawa Journal once described his domination of opposing players as leaving them in a state of being “nonplussed,” particularly when it came to his famous stick manoeuvre.

At the Hockey Hall of Fame in downtown Toronto, the skates Nighbor wore in the 1915 Stanley Cup Final when he led the Vancouver Millionaires to a title over the Ottawa Senators are displayed. At a nearby Tim Horton’s, a wall mural features Nighbor wearing his Pembroke Debaters jersey, highlighting 1947, the year he was inducted into the Hockey Fall of Fame.

It’s a reminder of how special a player Nighbor was, but it also begs the question-Why has Nighbor’s number six jersey never been retired by the Ottawa Senators? Nighbor spent most of his career with the Senators and several years ago he was recognized as being one of the organization’s most famous alumni through a banner that hangs high in the rafters of the Canadian Tire Centre. To truly honour Nighbor’s greatness, the next logical step would be to ensure his jersey number is never worn by another player.

Taking Nighbor’s number out of the mix so many years after he passed away is not without precedent. When the Toronto Maple Leafs celebrated their centennial year in 2016, they retired several numbers including former stars Hap Day, King Clancy and Turk Broda, decades after their careers had ended and they had passed away. For argument sake, a look at Day and Clancy’s resume suggest if the Leafs can retire their jersey numbers, the Senators should seriously consider pulling Nighbor’s number six from their dressing room.

Clancy played 16 seasons in the NHL, picking up 280 points. He helped the Leafs win their first Cup in 1932 and served as the team’s coach and club vice-president through a 55 year affiliation with the Toronto hockey club, joining the Hall of Fame in 1958. Day was part of six Stanley Cup championships with the Leafs, most of them as the team’s coach. He had 202 points during his playing career and was inducted into the Hall in 1961.

And then there is the Shawville Express. The Senators retired Frank Finnigan’s number 8 jersey when they played their first game in modern day history in 1992. Finnigan was the last surviving member of the 1926-27 Senators team that won a Stanley Cup and he had been involved in the advocacy campaign to bring back the Senators, but he passed away before the revived franchise returned to the ice. In his career, Finnigan had 203 points. In addition to his sweater retirement after his death, the hockey club also named the street that runs in front of the Canadian Tire Centre, Frank Finnigan Way.

In his career, Nighbor played 18 seasons in four different professional leagues, accumulating 255 goals. In his final season in 1929-30, Nighbor split it between the Senators and Toronto Maple Leafs. While the four players point production and team accomplishments are comparable, what separates Nighbor from Finnigan, Day and Clancy is his personal achievements, specifically the league wide awards that he won and his notoriety for the skill he demonstrated in perfecting the poke check.

The final NHL contract Nighbor signed, paying him more than $6,000 for the regular season, is displayed at the Pembroke Memorial Centre. After retiring he coached teams in Buffalo and London, before returning to Pembroke where he sold insurance and remained active as a minor hockey coach and supporter of the Senior Lumber Kings.

In 1940, the National Film Board came to Pembroke to shoot video of Nighbor teaching youngsters his famous hook check on the frozen Indian river. Wearing a fedora and an Ottawa Senators jersey, Nighbor is in his element, teaching the young boys on the same frozen patch of ice where he was introduced to the game. Ten years after he retired from playing, he continued to be sought out by national media for an opinion or demonstration of how the game should be played. He had a hold on those who loved the game, who missed watching him play.

It was on opening night at the Pembroke Memorial Centre on November 14, 1951 that Nighbor celebrated his induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame. Four years earlier he had missed his induction ceremony, and so his Hall of Fame scroll was presented to him in a pre-game ceremony, prior to the Senior Lumber Kings hosting the Montreal Canadiens. There would be six future Hall of Famers in the Habs line-up in that game including Maurice “the Rocket” Richard, Bernie “Boom Boom” Geoffrion and Elmer Lach.

When Frank Nighbor passed away from cancer in the spring of 1966, only a few weeks after giving a young Bobby Orr some tips from his hospital bed at the Pembroke General Hospital, his funeral attracted NHL royalty. Among those who attended the service at St. Columbkille’s Cathedral were Frank Selke, the General Manager of the Montreal Canadiens and Frank Finnigan, his illustrious Senators teammate from Shawville, Quebec. His final resting place is shaded by trees in a Catholic cemetery just outside Pembroke where his tombstone is modest, giving no indication that one of the greatest hockey players who ever lived is buried there. The name on the stone is Francis J. Nighbor, not “Frank” as he was known by thousands of Canadian hockey fans.

Nighbor is among three Hall of Fame players from Pembroke. The city is proud of his childhood friend Harry Cameron who won three Stanley Cups in Toronto and Hughie Lehman who competed in eight Stanley Cup challenges and was the first goaltender for the Chicago Black Hawks, but there is something very special about Nighbor.

In Pembroke, a street is named after him. His accomplishments are well documented through pictures and plaques at the city’s historic hockey rink, but across the nation, Nighbor remains a household name for anyone who follows the sport of hockey. His name and image appear in the most likely and unlikely places such as a wall portrait that dominates a coffee shop next door to the Hockey Hall of Fame in Ontario’s capital city or a mural on an old industrial building in downtown Buffalo.

Yes, the “Pembroke Peach” made his hometown proud and five decades after his death he hasn’t been forgotten. He was too good not to be remembered as the greatest hockey player Pembroke has produced. His legacy lives on.